| ABSTRACT = EXPLORING THEIR ORIGINS & ROLES IN JAPANESE DEATH RITES & FUNERARY ARTThe Thirteen Buddhist Deities (Jūsanbutsu 十三仏) are a purely Japanese convention. The standardized group of thirteen emerged in the mid-14th century, but in its formative years (12th & 13th centuries), the group's composition varied significantly and included only ten, eleven, or twelve members. The group is important to all schools of Japanese Buddhism. Even today, the thirteen are invoked at thirteen postmortem rites held by the living for the dead, and at thirteen premortem rites held by the living for the living. As shown herein, the thirteen are associated with the Seven Seventh-Day Rites 七七斎, the Six Realms of Karmic Rebirth 六道, the Buddhas of the Ten Days of Fasting 十斎日仏, the Ten Kings of Hell 十王, the Secret Buddhas of the Thirty Days of the Month 三十日秘仏, and other groupings. The Thirteen provide early examples of Japan's medieval honji-suijaku 本地垂迹 paradigm, wherein local deities (suijaku) are recognized as avatars of the Buddhist deities (honji). This classroom guide is unique in three ways: (1) it presents over 70 annotated images, arranged chronologically and thematically, from the 12th to 20th century; (2) it offers four methods to easily identify the individual deities; and (3) it provides visual evidence that the thirteen are configured to mimic the layout of the central court of the Womb World Mandala 中台八葉院. █ KEYWORDS. 十三仏 or 十三佛・十王・七七斎・七七日・中有・中陰・六齋日・六道 ・十斎日仏・三十日秘仏・本地垂迹 ・兵範記・中有記・ 預修十王生七経 ・地蔵十王経 ・佛説地藏菩薩發心因縁十王經・弘法大師逆修日記事 ・下学集. █ An Adobe PDF version (printable, searchable) is also available for download. |

Slide 1. Table of Contents. Condensed Visual Guide to Japan's Thirteen Buddhist Deities (Jūsanbutsu 十三仏). Cover photo shows modern piece for the family altar (butsudan 仏壇), used during Obon お盆 and other special times when praying for one's ancestors or living relatives or oneself (see Slide 59.) █ ABOUT THE AUTHOR. Mark Schumacher is an independent researcher who moved to Kamakura (Japan) in 1993 and still lives there today. His site, The A-to-Z Photo Dictionary of Japanese Religious Statuary, has been online since 1995. It is widely referenced by universities, museums, art historians, Buddhist practitioners, & lay people from around the world. The site's focus is medieval Japanese religious art, primarily Buddhist, but it also catalogs art from Shintō, Shugendō, Taoist, & other traditions. The site is constantly updated. As of August 2018, it contained 400+ deities & 4,000+ annotated photos of statuary from Kamakura, Nara, Kyoto, & elsewhere in Japan. I am not associated with any educational institution, private corporation, governmental agency, or religious group. I am a single individual, working at my own pace, limited by my own inadequacies. No one is looking over my shoulder, so I must accept full responsibility for any inaccuracies. I welcome feedback, good or bad. If you discover errors, please contact me. I rely on Chinese, Japanese & English sources. I cannot read Korean, Tibetan, Sanskrit, or Central Asian languages, so I must consult secondary sources of scholarship to underpin my findings. █ RESOURCES. To learn about the individual deities, please see the A-to-Z Photo Dictionary of Japanese Religious Art, or JAANUS (Japanese Architecture & Art Net Users System, or Digital Dictionary of Buddhism (login = guest). █ KEYWORDS. 十三仏 or 十三佛・十王・七七斎・七七日・中有・中陰・六齋日・六道 ・十斎日仏・三十日秘仏・本地垂迹 ・兵範記・中有記・ 預修十王生七経 ・地蔵十王経 ・佛説地藏菩薩發心因縁十王經・弘法大師逆修日記事 ・下学集.

Slide 1. Table of Contents. Condensed Visual Guide to Japan's Thirteen Buddhist Deities (Jūsanbutsu 十三仏). Cover photo shows modern piece for the family altar (butsudan 仏壇), used during Obon お盆 and other special times when praying for one's ancestors or living relatives or oneself (see Slide 59.) █ ABOUT THE AUTHOR. Mark Schumacher is an independent researcher who moved to Kamakura (Japan) in 1993 and still lives there today. His site, The A-to-Z Photo Dictionary of Japanese Religious Statuary, has been online since 1995. It is widely referenced by universities, museums, art historians, Buddhist practitioners, & lay people from around the world. The site's focus is medieval Japanese religious art, primarily Buddhist, but it also catalogs art from Shintō, Shugendō, Taoist, & other traditions. The site is constantly updated. As of August 2018, it contained 400+ deities & 4,000+ annotated photos of statuary from Kamakura, Nara, Kyoto, & elsewhere in Japan. I am not associated with any educational institution, private corporation, governmental agency, or religious group. I am a single individual, working at my own pace, limited by my own inadequacies. No one is looking over my shoulder, so I must accept full responsibility for any inaccuracies. I welcome feedback, good or bad. If you discover errors, please contact me. I rely on Chinese, Japanese & English sources. I cannot read Korean, Tibetan, Sanskrit, or Central Asian languages, so I must consult secondary sources of scholarship to underpin my findings. █ RESOURCES. To learn about the individual deities, please see the A-to-Z Photo Dictionary of Japanese Religious Art, or JAANUS (Japanese Architecture & Art Net Users System, or Digital Dictionary of Buddhism (login = guest). █ KEYWORDS. 十三仏 or 十三佛・十王・七七斎・七七日・中有・中陰・六齋日・六道 ・十斎日仏・三十日秘仏・本地垂迹 ・兵範記・中有記・ 預修十王生七経 ・地蔵十王経 ・佛説地藏菩薩發心因縁十王經・弘法大師逆修日記事 ・下学集. .

Slide 2. In a Nutshell. Any study of Japan’s Thirteen Buddhist Deities begins with a dilemma – there is scant textual evidence about the thirteen until the 15th century, making their study largely speculative. This guide therefore focuses on the “visual record,” presenting the oldest known artwork of the group during its formative period in the 12th & 13th & 14th centuries. Any study of the thirteen also requires an upfront caveat, for the term 十三仏, or 十三佛, is often mistakenly translated as “Thirteen Buddha” – the group includes five Buddha 仏, seven Bodhisattva 菩薩, and one Myō-ō 明王. Japan’s thirteen are a purely Japanese convention. They are not mentioned in the Taishō Buddhist Canon. Although the term 十三佛 (Thirteen Buddha) appears in 23 different texts of the canon, its usages show no known correlation with Japan’s thirteen. The latter preside over thirteen postmortem memorial rites that start on the 7th day after death and continue until the 33rd year after death (see Slide 3). The standard grouping appeared around the mid-14th C. after undergoing nearly two centuries of transition from 10 to 11 to 12 to 13 members. The group was popularized in the 15th C. and linked to both postmortem rites for the dead & premortem rites for the living. Despite the speculative nature of this topic, the group’s raison d’être can be convincingly shown via extant art. Here is a case where art seems to predate texts. Above seeds adapted from Shingon.org. |

|

|

![Slide 3. Conclusions Up Front. Four don't conform to modern dates ↑↑↑↑↑↑↑↑↑↑↑↑↑ Download chart in Excel or in Adobe PDF

1

Japan's 13 Buddhist Deities are a clever way to appeal to the largest possible congregation. The group's deities include:

SPECULATION

a

Traditional triad featuring Shaka (Historical Buddha), a Pure Land Triad featuring Amida, and an Esoteric Triad featuring Dainichi.

The 13th-14th centuries ushered in Buddhism for the commoner (Pure Land, Zen, Nichiren). The older esoteric Tendai school, meanwhile, was nearing the peak of its power. Tendai's arch rival, the Shingon school, was hence under pressure to retain its followers, and so it concocted the group of 13 Buddhist Deities, largely to counteract the growing popularity of the Pure Land, Zen & Nichiren schools & the rising power of Tendai. Amida (Pure Land) faith was [perhaps] the driving force in the adoption of China's 10 Kings of Hell & their linkage with 10 Buddhist deities. The 10 rites for the dead, based on China's 10 Kings, became a standard part of funerary rites in Tendai, Shingon, Pure Land, Zen & Nichiren traditions. Shingon later added three more deities & kings & rites (extending until the 33rd year after death) to remain relevant. The number 33 is associated with Kannon, a member of the 13. The number 33 involves the forms Kannon takes to save believers, as described in the Lotus Sutra (login = guest) -- the most popular scripture in all Asia. Today there are many 33-site pilgrimages in Japan to Kannon. For more on Kannon's 33 forms, click here. As for Ancestor Worship in Japan, 33 years marks the point when, says Hutchins pp. 64-65: "the deceased’s spirit passes from ‘distant’ to ‘remote’ & they become a full-fledged ancestor of the household." After 33 years, the dead are considered ancestral spirits. Buddhist rites are stopped. Today, death rites vary widely in Japan, but the 33rd year is still crucial.

b

A fourth triad is embedded as well -- the Buddhas of Three Ages 三世佛 -- featuring Amida (Past), Shaka (Present), Miroku (Future).

c

The three remaining deities (Fudō, Jizō, Yakushi) are among Japan's most beloved divinities.

d

Jizō & Miroku are paired (Jizō represents the Future Buddha Miroku); Jizō is also a popular member of the Pure Land school.

e

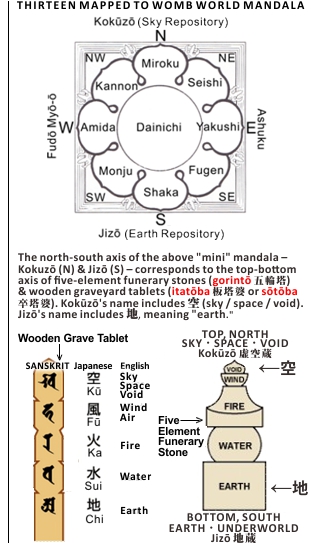

Jizō & Kokūzō are paired (Jizō as earth / matter and Kokūzō as space / void). This is unequivocally linked to China's five elements.

f

The Jizō and Kokūzō pairing is also unequivocally linked to Japan's five-tier memorial graveyard stones and wooden graveyard tablets.

g

Fudō and Dainichi are paired. Fudō is a manifestation of Dainichi. The two share the same holy day.

h

Yakushi and Ashuku are paired (perhaps); both are lords of the Eastern Paradise

2

The 13 Buddhist Deities were created by the Shingon school. There is no conclusive textual evidence, but all fingers point to Shingon.

a

The Dual World Mandala (composed of the Diamond World and Womb World mandalas) is especially important to the esoteric Shingon school.

b

The Womb World Mandala has "13 great courts" 十三大院. Mapping the 13 Deities into the central Womb Court yields a coherent group. See Slide 2.

c

Among the 13 Deities, the first (Fudō) & last three (Ashuku, Dainichi, Kokūzō) are revered primarily by Shingon & play key roles in mandala cosmology.

d

The moon is another big indicator. The "moon meditation" (GACHIRINKAN 月輪觀) is perhaps the most critical meditation practice in esoteric Buddhism.

e

In the esoteric Diamond World Mandala 金剛界曼荼羅, the divinities are often shown seated in the circle of a full moon.

f

As argued herein, the 13 Buddhist Deities are also likely derived from the 13 cycles of the moon (the intercalary 13th month).

g

Other indicators (non-Shingon) are the 13 articles kept by monks, the 13 contemplations, the 13 life stages (birth / adulthood), etc.

3

Sources for the Topmost Chart

(1) Scripture on Jizō and the 10 Kings (Bussetsu Jizō Bosatsu Hosshin Innen Jūō Kyō 佛説地藏菩薩發心因縁十王經), late 12th century, the earliest text that pairs the 10 Kings with Ten Buddhist deities; considered an apocryphal Japanese text; (2) Kōbō Daishi Gyakushu Nikkinokoto 弘法大師逆修日記事, early 15th century; Japanese text listing the 13 Buddhist deities, postmortem dates, & premortem dates; (3) Kagakushū 下学集 of 1444, a Japanese dictionary listing the 13 postmortem & premortem dates; (4) Jūsanbutsu Honji-Suijaku Kenbetsu Shaku 十三仏本地垂迹簡別釈 of early Edo (??); author & date unknown. (5) Hutchins has correlated the deity lists in most of these works in his Thirteen Buddhas: Tracing the Roots of the 13 Buddha Rites.

Related Groupings. (6) Ten Days of Fasting in 10th-C. (??) text Ten Purifying Days of Jizō Bodhisattva; (7) Secret Buddhist Deities of the 30 Days of the Month, a 10th-C. grouping from China that began appearing in 14th-C. Japanese texts; (8) Japan's Eight Buddhist Protectors of the Zodiac; popularized in the Edo era (1603 - 1867). They appear in the 1783 Butsuzō-zu-i (p. 70 online) 仏像図彙; (9) Sūtras & Texts on Jizō.](index_files/vlb_thumbnails1/conclusionsupfrontslidethreefinal.jpg)

|

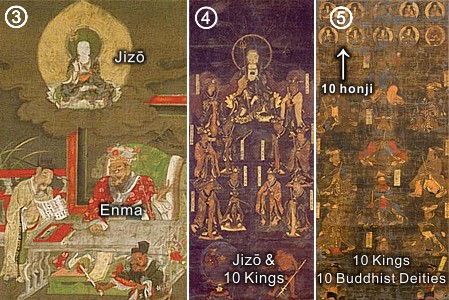

![Slide 4. Seven Seventh-Day Rites & Ten Kings of the Underworld. The Shichi-shichi-nichi chūin 七七日中陰 (seven X seven = 49 days between death & rebirth; login = guest) can be traced back to India. The term appears in the 4th-C. AD Yogacāra bhūmi-śāstra 瑜伽師地論 (login = guest); T.1579.30.282b1. The concept played a pivotal role in the 8th-C. Tibetan Book of the Dead. The seven-sevens also appear in Sanskrit & Pali texts dated to the 3rd/4th C. AD, including the Mahāvastu, Nidanakatha, Lalitavistara, & Mahabodhi Vamsa (date?). The latter work says the Historical Buddha fasted for 7 weeks (49 days) after his enlightenment. JAPANESE PRECEDENTS. ▀ 687 AD, 100th day memorial, Nihon Shoki 日本書紀; held at five temples for Emperor Tenmu 天武天皇. ▀ 735 AD, seven seventh-day rites 七七斎

mentioned by Emperor Shōmu 太上天皇 in the imperially commissioned historical record Shoku Nihongi 続日本紀 ▀ 757 AD, 1st year memorial 周忌, Shoku Nihongi; held for Emperor Shōmu 太上天皇 at Tōdaiji. ▀ 11th C. Shōryōshū 性霊集 (scroll 7), 3rd year rites for Kūkai; text also mentions 7th week & 1st year rites. By the end of the Heian era (794-1185 AD), there is textual evidence of memorial services connecting the 49 days with specific Buddhist deities, e.g., diary of Taira no Nobunori 平信範 (1112 - 1187) entitled Hyōhanki 兵範記.China's Ten Kings (Jūō 十王) appear in the Scripture on the Ten Kings 佛說預修十王生七經, compiled sometime in the 9th or early 10th C. AD. The dead undergo trials by the ten, with the first seven kings covering the crucial seven-week (49 day) period, followed by three more trials on the 100th day, the 1st year, & the 3rd year after death. The 100th day, 1st year, & 3rd year rites are found in the Chinese Book of Rites, said to be the work of Confucius (551–479 BC). The ancient term for the 100th day rite was 卒哭 (scroll 21). The ancient terms for 1st year and 3rd year rites were 小祥 & 大祥 (scroll 37). Writes Hutchins (p.52 & p.115): "The Scripture on the Ten Kings says that release [for the dead] can be obtained if the grieving family sends offerings to each ot the Ten Kings at the appropriate time. Further, it was thought to be even more beneficial to send offerings to the Ten Kings on one's own behalf while still living. In China, such offerings were made as far back as the 9th C. in the form of ten fasting days. Thus, this scripture promoted both postmortem & premortem rituals.” Teiser (1994, p. 53) notes that Taoist texts show the ritual of ten fasting days may have existed as far back as the 6th C. Both China & Japan (seemingly in tandem) "paired" the Ten Kings with Buddhist Deities, but the pairings show no known correspondence. Likewise, China/Japan (seemingly in tandem) paired Jizō 地蔵 & Enma 閻魔 (lord of hell).The Ten Kings arrived in Japan in the late Heian era (794-1185). Says Duncan R. Williams (p. 231): "The ten memorial rites for the dead, based on belief in the Ten Kings, were developed in Japanese apocryphal sūtras (login = guest) & later became a standard part of funerary rites in Shingon, Tendai, Zen, Jōdō, & Nichiren traditions. Paintings depicting the Ten Kings judging the dead were used for ritual or didactic purposes at times when the ancestral spirits were thought to return to this world." Artwork of the 13 Buddhist Deities appeared in Japan in the late 12th C. But texts referring to the 13 Deities do not appear until the Muromachi era (1392-1573). According to Ueshima Motoyuki 植島基行 (1975), it is unclear when the 13 Deity Rites were first used. In the Muromachi era, however, Ueshima says offering tablets (kuyōhi 供養碑) to the 13 Deities were built all around Japan. Ueshima believes these were built for the performance of Gyakushu Kuyō 逆修供養 (reverse performance benefits; aka "premortem" rites) by ordinary folk. Gyakushu, aka yoshu 預修, is performed while one is still alive to accrue benefits for oneself after death. In postmortem rites (Tsuizen Kuyō 追善供養) for the dead, the deceased only acquires 1/7th of the benefits, while the performer acquires 6/7th. In the Gyakushu, the performers acquire the full 7/7 benefits for themselves. For this reason the ritual is also called Shichibu Kentoku 七分全得. For more details on rituals involving the 13 Deities, see Karen Mack's Notebook. Elsewhere, Watanabe Shōgo 渡辺章悟 (1989, p. 210) estimates that, across Japan, there are more than four hundred medieval monuments (ihin 遺品) dedicated to the 13 Deities. Many of these are catalogued online by Kawai Tetsuo 河合哲雄. The 12th/13th C. Scripture on Jizō & Ten Kings 佛説地藏菩薩發心因縁十王經 (see Tripitaka CBETA) is the oldest text that pairs the kings with ten Buddhist deities. It is considered a Japanese text but its precise origin is unknown. In medieval times, China too "paired" its ten kings with Buddhist deities (Slide Five), but the China / Japan pairings show no correspondence. The Jizō = Enma link likely occurred in China before Japan. By the mid-14th C., Japan had added three more deities, three more kings, & three more memorial rites (i.e., 7th, 13th, 33rd years). These new deities & rites are found only in Japan. They probably originated with Japan’s Shingon school, but were widely appropriated by other schools.](index_files/vlb_thumbnails1/slidefourtenkingsb.jpg)

The Shichi-shichi-nichi chūin 七七日中陰 (seven X seven = 49 days between death & rebirth; login = guest) can be traced back to India. The term appears in the 4th-C. AD Yogacāra bhūmi-śāstra 瑜伽師地論 (login = guest); T.1579.30.282b1. The concept played a pivotal role in the 8th-C. Tibetan Book of the Dead. The seven-sevens also appear in Sanskrit & Pali texts dated to the 3rd/4th C. AD, including the Mahāvastu, Nidanakatha, Lalitavistara, & Mahabodhi Vamsa (date?). The latter work says the Historical Buddha fasted for 7 weeks (49 days) after his enlightenment. JAPANESE PRECEDENTS. ▀ 687 AD, 100th day memorial, Nihon Shoki 日本書紀; held at five temples for Emperor Tenmu 天武天皇. ▀ 735 AD, seven seventh-day rites 七七斎 mentioned by Emperor Shōmu 太上天皇 in the imperially commissioned historical record Shoku Nihongi 続日本紀 ▀ 757 AD, 1st year memorial 周忌, Shoku Nihongi; held for Emperor Shōmu 太上天皇 at Tōdaiji. ▀ 11th C. Shōryōshū 性霊集 (scroll 7), 3rd year rites for Kūkai; text also mentions 7th week & 1st year rites. By the end of the Heian era (794-1185 AD), there is textual evidence of memorial services connecting the 49 days with specific Buddhist deities, e.g., diary of Taira no Nobunori 平信範 (1112 - 1187) entitled Hyōhanki 兵範記. FOR MORE: See Karen Gerhart, pp. 19-26. | China's Ten Kings (Jūō 十王) appear in the Scripture on the Ten Kings 佛說預修十王生七經, compiled sometime in the 9th or early 10th C. AD. The dead undergo trials by the ten, with the first seven kings covering the crucial seven-week (49 day) period, followed by three more trials on the 100th day, the 1st year, & the 3rd year after death. The 100th day, 1st year, & 3rd year rites are found in the Chinese Book of Rites, said to be the work of Confucius (551–479 BC). The ancient term for the 100th day rite was 卒哭 (scroll 21). The ancient terms for 1st year and 3rd year rites were 小祥 & 大祥 (scroll 37). Writes Hutchins (p.52 & p.115): "The Scripture on the Ten Kings says that release [for the dead] can be obtained if the grieving family sends offerings to each ot the Ten Kings at the appropriate time. Further, it was thought to be even more beneficial to send offerings to the Ten Kings on one's own behalf while still living. In China, such offerings were made as far back as the 9th C. in the form of ten fasting days. Thus, this scripture promoted both postmortem & premortem rituals.” Teiser (1994, p. 53) notes that Taoist texts show the ritual of ten fasting days may have existed as far back as the 6th C. Both China & Japan (seemingly in tandem) "paired" the Ten Kings with Buddhist Deities, but the pairings show no known correspondence. Likewise, China/Japan (seemingly in tandem) paired Jizō 地蔵 & Enma 閻魔 (lord of hell). | The Ten Kings arrived in Japan in the late Heian era (794-1185). Says Duncan R. Williams (p. 231): "The ten memorial rites for the dead, based on belief in the Ten Kings, were developed in Japanese apocryphal sūtras (login = guest) & later became a standard part of funerary rites in Shingon, Tendai, Zen, Jōdō, & Nichiren traditions. Paintings depicting the Ten Kings judging the dead were used for ritual or didactic purposes at times when the ancestral spirits were thought to return to this world." Artwork of the 13 Buddhist Deities appeared in Japan in the late 12th C. But texts referring to the 13 Deities do not appear until the Muromachi era (1392-1573). According to Ueshima Motoyuki 植島基行 (1975), it is unclear when the 13 Deity Rites were first used. In the Muromachi era, however, Ueshima says offering tablets (kuyōhi 供養碑) to the 13 Deities were built all around Japan. Ueshima believes these were built for the performance of Gyakushu Kuyō 逆修供養 (reverse performance benefits; aka "premortem" rites) by ordinary folk. Gyakushu, aka yoshu 預修, is performed while one is still alive to accrue benefits for oneself after death. In postmortem rites (Tsuizen Kuyō 追善供養) for the dead, the deceased only acquires 1/7th of the benefits, while the performer acquires 6/7th. In the Gyakushu, the performers acquire the full 7/7 benefits for themselves. For this reason the ritual is also called Shichibu Kentoku 七分全得. For more details on rituals involving the 13 Deities, see Karen Mack's Notebook. Elsewhere, Watanabe Shōgo 渡辺章悟 (1989, p. 210) estimates that, across Japan, there are more than four hundred medieval monuments (ihin 遺品) dedicated to the 13 Deities. Many of these are catalogued online by Kawai Tetsuo 河合哲雄. The 12th/13th C. Scripture on Jizō & Ten Kings 佛説地藏菩薩發心因縁十王經 (see Tripitaka CBETA) is the oldest text that pairs the kings with ten Buddhist deities. It is considered a Japanese text but its precise origin is unknown. In medieval times, China too "paired" its ten kings with Buddhist deities (Slide Five), but the China / Japan pairings show no correspondence. The Jizō = Enma link likely occurred in China before Japan. By the mid-14th C., Japan had added three more deities, three more kings, & three more memorial rites (i.e., 7th, 13th, 33rd years). These new deities & rites are found only in Japan. They probably originated with Japan’s Shingon school, but were widely appropriated by other schools. |

![Slide 6. Ten Kings & Ten Buddhist Counterparts 十仏十王図, 13th Century. Cartouche Style, Standard Grouping. PHOTO: Nara National Museum /// Identifications. Says Says Hirasawa (p. 26): "As correspondences of originals (honji 本地) to manifestations (suijaku 垂迹) settled into standard formulae, the importance and size of the honji increased. This reached an extreme in a 14th-century painting of a colossal Jizō appearing to stand directly on top of Enma's head [see Nihon no Bijutsu 日本の美術, No. 313, Shibundō, 1992]. In another, later medieval cult, three buddhas associated with esoteric Buddhism joined the ten honji of the kings. Eventually the suijaku completely fell away from the iconography, leaving only images of the thirteen buddhas for mortuary rites, without visual references to judgment in hell."](index_files/vlb_thumbnails1/tenkingstenbuddhistcounterparts13thcenturynaranationalmuseum2.jpg)

![Slide 9. Ten Judges of Underworld with Jizō (in center). Late 12th Century. Stone statues at Usuki, Ōita, Japan. PHOTO: JapanTravel. Says Hank Glassman, pp. 18-19: "The idea that Jizō and Enma (lord of the world of the dead) are different manifestations of the same entity stems from the Japanese practice, well established by the time of the composition of The Scripture on Jizō and the Ten Kings, of drawing equivalencies between Buddhist deities and local ones......The equivalence between Jizō and Enma was one that was extremely well known and widely cited in premodern Japan in both text and image. In Chinese and Korean paintings of the ten kings, Jizō was often accorded a central position. What is quite different in Japan is that Jizō is represented at the court of Enma, the fifth and greatest king, where he pleads on behalf of the deceased.....The immense popularity of Jizō in medieval and early modern Japan was fueled in large part by the belief that Jizō was the best advocate for the sinner being judged before the magistrate Enma, since Jizō was in fact the alter ego of this terrifying and intimidating judge. This relationship, described in the The Scripture on Jizō and the Ten Kings, is made explicit in Japanese paintings of Enma or Jizō. [Slides 10~11]](index_files/vlb_thumbnails1/jizotenkingsusukioita.jpg)

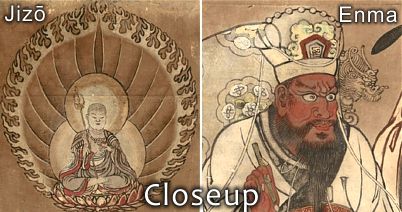

Slide 10. Says Hutchins (p. 55): “Although the Ten Kings were not originally conceived as Buddhist deities, Jizō was often a central figure in many of the pictures and artworks of the Ten Kings imported to Japan in the early Heian period. To be able to understand this, we need to take into consideration Jizō’s interpretation as an alter ego of King Yama 閻魔 (Jp. = Enma), the lord of the world of the dead. In many of the paintings of the courts of the Ten Kings produced in medieval Japan, Jizō is often superimposed above the fifth court of hell to demonstrate his role as the twin of King Yama. Such an association suggested that other kings could also potentially be seen as manifestations of Buddhist deities, and this view was made explicit in The Scripture on Jizō and the Ten Kings. Like the earlier Scripture on the Ten Kings, it outlines the journey of the deceased’s spirit through ten courts of purgatory. The real importance of this text for our study is that it appears to be the earliest written record that pairs the Ten Kings with Buddhist deities. This is commonly referred to as an example of honji suijaku 本地垂迹 — a kind of assimilation process where the Ten Kings are seen as traces (suijaku), or alternative incarnations, of the original Buddhas (honji).”

|

|

Six Realms & Ten Kings 六道十王図, Gokuraku Jigoku zu 極楽地獄図, 16th-17th century, Chōgaku-ji Temple 長岳寺, Nara Prefecture, set of ten scrolls. Writes Hirasawa (p. 26): "The ten kings, each with its honji, line up across the top of the scrolls, representing the process of judgment through time. Vast scenes of hell and the six realms below the kings evoke a spatial cosmology, subject to the temporal framework of judgment, and the scrolls conclude with a bridge leading from Abi hell (阿鼻地獄, lowest hell, hell of no interval) directly to a raigō 来迎 ("greeting") by Amida and his entourage, welcoming sinners to the Pure Land. According to Takasu Jun 鷹巣純, these images do not merely patch together two traditions; they reconfigure and reinvigorate them as a mandatory circuit through hell that ends in salvation -- and that audiences can experience vicariously." PHOTO: Nara Women's University Academic Info Center.

Six Realms & Ten Kings 六道十王図, Gokuraku Jigoku zu 極楽地獄図, 16th-17th century, Chōgaku-ji Temple 長岳寺, Nara Prefecture, set of ten scrolls. Writes Hirasawa (p. 26): "The ten kings, each with its honji, line up across the top of the scrolls, representing the process of judgment through time. Vast scenes of hell and the six realms below the kings evoke a spatial cosmology, subject to the temporal framework of judgment, and the scrolls conclude with a bridge leading from Abi hell (阿鼻地獄, lowest hell, hell of no interval) directly to a raigō 来迎 ("greeting") by Amida and his entourage, welcoming sinners to the Pure Land. According to Takasu Jun 鷹巣純, these images do not merely patch together two traditions; they reconfigure and reinvigorate them as a mandatory circuit through hell that ends in salvation -- and that audiences can experience vicariously." PHOTO: Nara Women's University Academic Info Center.

![Slide 26. 1359 CE. Non-standard grouping. Enmeiji 延命寺, Sakatashi City 酒田市, Yamagata Prefecture, Japan. Twelve Buddhist deities symbolized by their Sanskrit seed syllables. Says Steven Hutchins (Masters Degree, SOAS, 2013) in his book Thirteen Buddhas (pp. 78~80): "Another example that further illustrates this transitional period [editor: from 10, to 11, to 12, to 13 deities] is a stone memorial located in a Shingon temple in Yamagata prefecture called Enmeiji 延命寺. The inclusion of twelve deities suggest a movement towards the Thirteen Buddhas, but the centrality of the Amida triad in this monument indicates that this could also be looked on as Ten Buddhas with Amida as the main honzon -- the Amida triad counting as one single Buddha. The appearance of Kongō Satta provides another problem for researchers attempting to link this monument with the Thirteen Buddha Rites. Kawakatsu says that although the addition of Ashuku is consistent with a general transition towards the Thirteen Buddhas, he is at a loss to explain why Kongō Satta should be included. One possibility is that the Sanskrit inscription for Kongō Satta could have been mistakenly transmitted instead of Dainichi’s." Mark here. Kongō Satta appears in a Dainichi Triad in the Diamond World Mandala, so Kongō Satta’s appearance can be justified. Inscription = Unable to find it on web. PHOTO: This J-site. Also see Kawakatsu Seitarō 川勝政太郎. 1969. Jūsanbutsu shinkō no shiteki tenkai 十三仏信仰の史的展開 (Evolution of Jūsanbutsu Faith), Journal of Ōtemae College 大手前女子大学論集, no. 03, pp. 94-111.](index_files/vlb_thumbnails1/enmeijijunison1359.jpg)

1. Ōtsu-e, Edo era. Zigzag Pattern. Standard Grouping. PHOTO: Ōtsu City Museum of History 大津市歴史博物館. 2. Ōtsu-e, Edo era. Zigzag Pattern. Standard Grouping. PHOTO: Machida City Museum, Tokyo 町田市立博物館蔵 3. Ōtsu-e, Edo era. Zigzag Pattern. Standard Grouping. PHOTO: Momose Osamu 百瀬治氏 Collection, HiHuMi Art. 4. Learn more about Ōtsu-e at JAANUS.

- Evans-Wentz, W.Y. (translator). 1927. Tibetan Book of the Dead. Commonly dated to the 8th century CE.

- Gerhart, Karen. 2009. The Material Culture of Death in Medieval Japan. (pp. 19-26). Honolulu, University of Hawaii Press.

- Glassman, Hank. 2012. The Face of Jizō: Image and Cult in Medieval Japanese Buddhism. Honolulu, University of Hawaii Press.

- Hiraswa, Caroline. 2008. The Inflatable, Collapsible Kingdom of Retribution. A Primer on Japanese Hell Imagery and Imagination. Monumenta Nipponica, Vol. 63, No.へぎヴぇ 1 (Spring, 2008).

- Hutchins, Steven. 2015. The 13 Buddhas: Tracing the Roots of the Thirteen Buddha Rites.

- Kawai Tetsuo 河合哲雄. He catalogs hundreds of memorial stones at 13 Buddhist Deities and at Stone Buddhist Statues.

- Kawakatsu Seitarō 川勝政太郎. 1969. Jūsanbutsu shinkō no shiteki tenkai 十三仏信仰の史的展開 (Evolution of Jūsannbutsu Faith), Journal of Ōtemae College 大手前女子大学論集, no. 03, pp. 94-111.

- Mack, Karen. 2000. Notes on an article by Ueshima Motoyuki about the Thirteen Buddhist Deities.

- McCormick, Melissa. 2009. Tosa Mitsunobu and the Small Scroll in Medieval Japan. See chapter two for a discussion of how paintings of the thirteen were used in the early 16th century.

- Miyasaka Yūkō 宮坂宥洪. 2011. Jūsanbutsu shinkō no igi 十三仏信仰の意義 (Significance of Jūsanbutsu Faith). Gendai Mikkyō, no 23 現代密教第23号目次.

- Ogurisu Kenji 小栗栖健治. 1991. Jūsanbutsu zu ni tsuite: jigoku e o egaku sakurei 十三仏図について-地獄絵を描く作例 (Concerning Jūsanbutsu Paintings: Examples of Hell Depictions) Shikai: Hyōgo kenritsu rekishi hakubutsukan kiyō, jinkai 3, pp. 29-47, March 1991.

- Payne, Richard. 1999. Shingon Services for the Dead in Religions of Japan in Practice, pp. 159-165.

- Phillips, Quitman. 2003. Narrating the Salvation of the Elite: The Jōfukuji Paintings of the Ten Kings. Ars Orientalis, Vol. 33, pp. 120-145.

- Picken, Stuart D.B. 2016. Parallel Worlds: Folk Religion, Life & Death in Japan. A serialised monograph on “Death in the Japanese Tradition: A Study in Cultural Evolution and Transformation.“

- Shimizu Kunihiko 清水邦彦. 2002. Jizō jūōkyō kō 地蔵十王経考 (Reflections on the Scripture of Jizō and the Ten Kings). Journal of Indian and Buddhist Studies, 51 (1) pp. 189-194.

- Somegawa Eisuke 染川英輔. 1993. Mandara Zuten 曼荼羅図典. Published by Daihorinkaku 大法輪閣. (Illustrated Dictionary of Japan’s Dual World Mandala).

- Stone, Jacqueline and Walter, Mariko Namba, editors. 2008. Death and the Afterlife in Japanese Buddhism. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

- Takeda Kazuaki 武田和昭. 1990. Jūsanbutsu zu no seiritsu ni tsuite: Jūichison mandara zu kara no tenkai 十三仏図の 成立について : 十一尊曼荼羅図からの展開 (Concerning the Origins of the Thirteen Buddhist Deities: Their Development from the Mandala of Eleven Honored Ones), pp. 22-24. Mikkyō Bunka 169 (Feb. 1990).

- Takeda Kazuaki 武田和昭. 1994. Jūsanbutsu zu no seiritsu saikō: Okayama, Kiyamaji zō jūō jū honjibutsu zu o chūshin to shite 十三仏図の成立再考: 岡山・木山寺蔵十王十本地仏図を中心として (Reconsideration on Genesis of Jūsanbutsu Art of Thirteen Buddhas). Published by Mikkyō Bunka 密教文化 188, pp. 29-60.

- Takeda Kazuaki 武田和昭. 1997. Yoshujūō shōshichikyō no zuzōteki tenkai: Ōsaka Hirokawadera zō Jūō kyō hensōzu o chūshin to shite 預修十王生七経の図像的展開: 大阪・弘川寺蔵十王経変相図を中心として (Iconographic Development of the Ten Kings’ Sūtra: Centering on the Illustrated Ten-Kings’ Sūtra Paintings of Hirokawa-dera in Osaka). Published by Museum 547, pp. 5-27.

- Teiser, Stephen. 1994. The Scripture on the Ten Kings and the Making of Purgatory in Medieval Chinese Buddhism. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

- Tibetan Book of the Dead. 8th century. See “Evans-Wentz” above.

- Ueshima Motoyuki 植島基行. 1971. Jūsanbutsu seiritsu e no tennkai 十三仏成立への展開 (How the Thirteen Buddhas Came into Existence). Published by Mikkyō Bunka 密教文化 94, pp. 14-18.

- Ueshima Motoyuki 植島基行. 1975. Jūsanbutsu ni tsuite 十三仏について(上) & 十三仏について(下), Concerning 13 Buddha. Kanazawa Bunko Research 金澤文庫研究, No. 234 (Nov. 1975) and No. 235 (Dec. 1975). He gives 4 theories on group's origin that credit Tendai monk Ennin 圓仁 (794-864), Shingon monk Myōe 明慧 (1173-1232), Zen monk Monkan 文観 (1278-1357), or Shingon monk Manbei 満米 (early Heian).

- Wakabayashi Haruko 若林晴子. 2009. Officials of the Afterworld: Ono no Takamura and the Ten Kings of Hell, Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, 36/2: pp. 319-342.

- Watanabe Shōgo 渡辺章悟. 1989. Tsuizen kuyō no Hotokesama Jūsanbutsu Shinkō 追善供養の仏さま十三仏信仰 (The Buddhas of Memorial Services: Jūsanbutsu Faith). Hokushindō.

- Watarai Zuiken 渡会瑞顕, editor. 2012. Jūsanbutsu no sekai tsuizenkuyō no rekishi・shisō・bunka 十三仏の世界— 追善供養の歴史・思想・文化 (Realm of 13 Buddhas: History, Thought, Culture). Nonburusha.

- Williams, Duncan Ryūken. 2008. Funerary Zen: Sōtō Zen Death Management in Tokugawa Japan, in Stone and Walter 2008, pp. 207-246.

- Yajima Arata 矢島新. 1990. Gunma-ken ka no butsuga kara: Numatashi Shōkakuzō Jūōzu to Jyūsanbutsu Seiritsu no Mondai 群馬県下の仏面から: 沼田市正覚寺蔵十王図と十三仏成立の問題 (Ten Kings' Art and the Origins of the Thirteen Buddhist Deities: Shōgaku-ji Temple, Numata City). Bulletin of Gunma Prefectural Women’s College 群馬県立女子大学紀要, No. 10, pp.63-73.

Slide 83. MANTRAS FOR ALL THIRTEEN | Slide 83. MERITS OF WORSHIPPING THE THIRTEEN |

|

功徳-生命の尊さを知らしめ、生まれながらにそなえている自身の清らかな心に気づかせてくれます 功徳-福徳と智慧を授け、生命の根源に気づかせてくれます |

---------------------------- END SLIDESHOW ----------------------------

↓↓ QUICK LINKS TO INDIVIDUAL DEITIES & IMPORTANT HELL TOPICS ↓↓

|

Thirteen Buddhist Deities (十三仏) Thirteen Buddhist Deities (Jūsanbutsu 十三仏 or 十三佛) -- five Buddha 仏, seven Bodhisattva 菩薩, and one Myō-ō 明王 -- are important to all schools of Japanese Buddhism. They likely originated with Japan's Shingon school of Esoteric Buddhism. The Thirteen are invoked at 13 postmortem memorial services held over a 33-year period by the living for the dead. They are also invoked in premortem rites by the living for the living. The Thirteen are closely associated with China's 10 Kings of Hell. Japan's Grouping of 13 appeared around the 14th century, and is considered a purely Japanese convention. |

||||

|

Judgement |

Name of |

Kanji & |

Honjibutsu |

|

|

1st week, 7th day |

Shinkō-ō |

秦広王 |

不動明王 |

|

|

2nd week, 14th day |

Shokō-ō |

初江王 |

釈迦如来 |

|

|

3rd week, 21st day |

Sōtei-ō |

宋帝王 |

文殊菩薩 |

|

|

4th week, 28th day |

Gokan-ō |

五官王 |

普賢菩薩 |

|

|

5th week, 35th day |

Enma-ō |

閻魔王 |

地蔵菩薩 |

|

|

6th week, 42nd day |

Henjyō-ō |

変成王 |

弥勒菩薩 |

|

|

7th week, 49th day |

Taizan-ō |

泰山王 |

薬師如来 |

|

|

During the seven weeks following one’s death, tradition asserts that the soul wanders about in places where it used to live. On the 50th day, however, the wandering soul must go to the realm where it is sentenced (one of the six realms). The 49th day is thus the most important day, when the deceased receives his/her karmic judgment and, on the 50th day, enters the world of rebirth. A service is held to make the “passage” as favorable as possible. Prayers are thereafter offered at special intervals, and performed indefinitely starting in the 13th year. Source: Flammarion, p. 340. |

||||

|

100th day |

Byōdō-ō |

平等王 |

観世音菩薩 |

|

|

1st year |

Toshi-ō |

都市王 |

勢至菩薩 |

|

|

3rd year |

Gotōtenrin-ō |

五道転輪王 |

阿弥陀如来 |

|

|

Three more hell kings, along with three more Buddhist deities, were added to the above ten. |

||||

|

7th Year |

Renjō-ō |

れんじょうおう |

阿閦如来 |

|

|

13th Year |

Bakku-ō |

ばっくおう |

大日如来 |

|

|

33rd Year |

Jion-ō |

じおんおう |

虚空蔵菩薩 |

|

|

NOTES

| ||||

|

OVERVIEW. DAY OF GREAT IMPORTANCE. On the 35th day following death, Enma-ō (Skt. = Yama, the 5th Hell King and Lord of the Underworld, often shown holding the Wheel-of-Life in Tibetan Tanka) makes his ruling after hearing the judgments passed down by the first four kings. Offerings by living relatives are especially important on the 35th day following death, as this is the day the defendant is sentenced by Enma to one of six realms of existence -- (1) Hell; (2) Hungry Ghosts; (3) Animals; (4) Asura; (5) Human Beings; (6) the heavenly Deva realm . All six realms are stages of suffering, even the heavenly realm of the Deva, who it is said suffer from pride. The sixth judge of hell, Henjo-o, decides your placement within the realm you are sentenced (reborn) into. For example, for those to be reborn into the human realm, Henjo-o may sentence you to be reborn as a wealthy or poor person, as a peaceful or violent person. The 7th judge, Taizan-o, dictates the conditions of rebirth, such as one’s life span and one’s sex, male or female. During the seven weeks following one’s death, tradition asserts that the soul wanders about in places where it used to live. On the 50th day, however, the wandering soul must go to the realm where it was sentenced (one of the six realms). Even so, for those sentenced to the lower realms, there is a way out. Among believers of the Jōdo Pure Land sect (Amida faith), those sentenced to the realm of hell, hungry ghosts, animals (beasts), or Asura (the realm of anger) may gain salvation, but only if their living relatives hold a memorial on the 100th day following their death, and another on the first year following their death, and yet another on the third year following their death. Enma is considered the most important of the ten judges, and in artwork Enma is thus frequently placed in the center. |

||||

|

At Ennoji Temple in Kamakura, one can view statues of the Excuse Jizō and the 10 Judges of Hell. Most of these statues were made in the Edo Period (1603-1868 AD). Ennoji Temple is the 8th site on the Pilgrimage to 24 Kamakura Sites Sacred to Jizo. Statues of the Ten Kings can also be seen at Engakuji Temple. The Kamakura Museum (Kamakura Kokuhokan, inside Tsurugaoka Hachimangu Shrine) also exhibits a number of hell-related statues from Ennoji Temple.

|

||||

For more on Japan's hell cosmology, deities & demons,

see SAI NO KAWARA (Riverbed of the Netherworld).

First published July 25, 2018. Copyright Mark Schumacher.